“Lads! Run away ! There’s a snake in the grass!”

An alarming welcome to a garden, you might think! But so translates the Latin quotation that heads John Evelyn’s handwritten list of classical mottoes displayed around Sayes Court Garden: “O pueri fugite hinc, latet anguis in herba.” I can only speculate why he chose to use this particular line. Was it a serious warning about the darker side of nature? Or was it perhaps meant as a joke, and the snake a harmless painted or sculpted one, a bit like this lovely one I spotted recently at Hampton Court Palace Flower show?

Anguis in herba

The quote is a line from Virgil’s Eclogues (3.93), uttered in an enigmatic singing match between two shepherds. In the seventeenth century, anyone with a good education would have known where most of Evelyn’s quotations came from, and been able to appreciate their aptness for the situation in which he had placed them. A walk around Sayes Court garden would therefore have been not just a horticultural experience but also a carefully thought-through literary, philosophical, and even spiritual one.

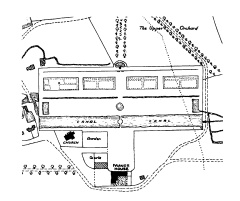

Alas! There’s no sign of any such depth in the latest tweaks to the masterplan for Convoys Wharf. I listened with dismay to the smooth talk on their website about a “contemporary interpretation” of Sayes Court garden, which seems to translate as – wait for it – a couple of lines of trees leading out of the present park, and a few lines in the pavement. All this so-called “consultation,” but no-one among the developers actually listens. So I’ll spell it out in simple terms. We want an authentic SEVENTEENTH CENTURY RESTORATION of Sayes Court Garden, not a minimalist 21st century “interpretation” for goodness’ sake – there are plenty of those around already!

If, against the odds, my dream of a restoration were actually to happen, Evelyn’s mottoes would be part of it – with English translations to hand, perhaps on the backs. The original mottoes would probably have been painted on wood, and I imagine them hanging from branches or perhaps mounted on walls or fences. Their reincarnations could be combined with statues, particular planting, and so on. Plenty of scope for ingenuity and art…

Here, in the order Evelyn wrote them, are some of the rest of the garden mottoes, with their references as I’ve managed to trace them, translations, and a few comments of my own in square brackets.

Perpetual spring

2. Hic ver perpetuum, varios hic flumina

circumfundit humus flores…

(Virgil, Eclogue IX)

“Here is shining spring,

Here amid streams blow many-coloured flowers.”

[Now, this is more the sort of message one would expect to read!

This eclogue continues: “Here poplars hoary-tressed droop o’er the cave,

And lo! the limber vine plaits leafy bowers.

Hither! and let mad billows beat the strand.”

The mad billows of the nearby Deptford Strand?]

Spring by her flowers he knows

3. Ver sibi flore notat

(Claudian, carmina minora 20)

“Spring by flowers he knows.”

This poem is about an old man who stayed close to home throughout his life. Evelyn’s friend Abraham Cowley translated it and included it in his essay, “The dangers of an honest man in much company.” The meaning of the line is that the wise person marks the passage of time by the changes in nature, not by man-made events (or contraptions, for that matter). The poem continues:

“He measures time by landmarks, and has found

For the whole day the dial of his ground.”

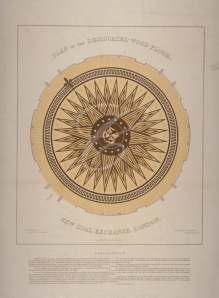

Since “dial” could mean a sundial, my bet is that this motto was on or near a sundial in the garden. We know there was one at the centre of the parterre.

17th c. Garden Party

4. Inter gestantium complexus, inter adorantium oscula, inter plausus admirantium: hic [?] vis quidem, at [?] gloriosa vita! – Nosegay.

(Claudius Batholomaeus Morisotus: Peruviana, published 1645)

“Among the embraces of joyful people, among the kisses of the adoring, among the applause of admirers – this is violence indeed, but a famous life!”

The above translation is my own. It’s provisional, especially where I’m not sure of his handwriting. Evelyn has apparently adapted a passage from p. 319 of the above book, a Latin novel nominally set in Peru but actually, it seems, referring to political figures in France. The second half of the motto recalls the last words of Julius Caesar as his assassins plunged at him: “Ista quidem vis est” “This is violence!”

“Nosegay”, written right after the motto, probably means that this motto was in his private garden, part of whose function was to provide flowers for making nosegays or posies. If I read this right, it offers us an interesting insight into how he saw his own and his garden’s celebrity.

More garden mottoes next time.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Many thanks to Frances Harris for kindly sending me photocopies of Evelyn’s motto lists.

Anyone who knows any more about 17th c. house and garden mottoes, or knows of any surviving examples or images of them, I’d love to hear from you. Also from those whose Latin is less rusty than mine.

Read Full Post »