Damaged mulberry, Sayes Ct. Park

I have been meaning for a while to post more about the ancient mulberry that first drew my attention to Sayes Court Park. Now it has sadly suffered some major damage, losing a bough that appears to have been rotting for some time. Reporting the loss, the South London Press calls it “Peter the Great’s tree”, predictably trotting out the persistent legend that it was planted by the Russian czar. As I’ve said before, I think this is extremely unlikely, because Peter showed little interest in anything other than wrecking the garden during his brief stay at Sayes Court. In my opinion, the legend probably conflates the lingering memory of Peter’s visit with the tree that had become emblematic of the lost garden.

The dubious association with Peter goes back at least to the mid-nineteenth century. Peter Cunningham’s 1850 Handbook of London refers to “a tree said to have been planted by Peter the Great when working in this country as a shipwright”. On the other hand, Nathan Dews’s History of Deptford, published in 1883, quotes an unnamed 1833 piece or book by one Alfred Davis that described (presumably the same?) tree as follows: ” A forlornly looking, ragged mulberry tree, standing at the bottom of Czar Street, was the last survivor of the thousands of arborets planted by “sylva” Evelyn in the gardens and grounds surrounding his residence at Deptford.” Planted by Evelyn, not by Peter the great, note! Of course, the present mulberry tree is not at the bottom of Czar Street, but of Sayes Court St., but perhaps we shouldn’t expect too much geographical exactness – it surely is the same tree that we see today?

Charlton House Mulberry planted 1608

Could the mulberry really have been part of Evelyn’s planting? There are two angles we can approach this question from: the age of the tree, and whether its siting matches what we know of the garden’s layout in the seventeenth century. If the tree’s annual growth rings could be counted, we’d know its exact age – but that would mean drilling into it, which I wouldn’t advocate! But if you compare its girth and general gnarled state with the mulberry at nearby Charlton House, known to date from 1608, it does seem to be of similar character.

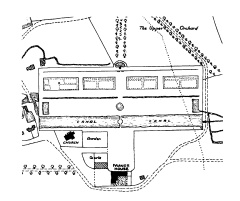

As for its siting, it’s difficult to be certain, but It is most probably in the area known then as the Broomefield, a long plot of land that was only incorporated into the garden a few decades after Evelyn first laid it out. (On the plans from the 1690’s it is divided into squares edged with unspecified trees). Still, it is quite close to the part of the garden that formed the Great Orchard, which Evelyn says in the key to his 1653 plan he planted with “300 fruit trees of the best sorts mingled”. There could have been a mulberry among them, although I think they were then still not common. The only mulberry Evelyn specifically records is the one he notes as “the mulberry”, on the island in the lake, some distance away at the northern edge of the garden. So it is doubtful whether there were any others, at least at that time. Of course, the garden changed over the decades, and as I have already described, part of the Great Orchard by 1692 had become another grove, interlaced with geometric walks. However, if in this new grove Evelyn kept some or all of the by-then mature and thickly-planted fruit trees of the earlier orchard and merely inserted paths between them, it is possible our mulberry survives from then. My own view, for what it’s worth, is that the mulberry was either in Evelyn’s garden, or is a direct descendant of one that was. Without a detailed planting record, though, the question must remain open.

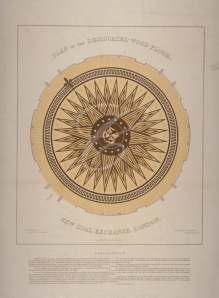

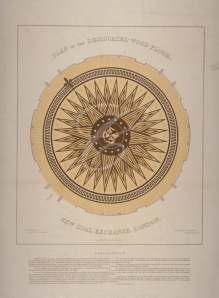

New Coal Exchange floor design

Once the rest of the garden had gone, a single surviving tree would inevitably become a potent reminder of what had been lost, gradually accruing greater poignancy as the site around it became more and more ravaged by development. Dews mentions that in his time a fragment of the mulberry was in the custody of Hastings Hicks, the Evelyns’ agent at their estate office on Evelyn St. Were people helping themselves to bits of the old tree as souvenirs, or had parts of it started to rot and drop off even back then?

The scavenging went on even at the highest level: Dews and Cunningham both noted that a piece of the tree was taken and used as part of the design of the main floor of the New Coal Exchange, constructed between 1847 to 1849 in Lower Thames Street. It formed the blade of the dagger in the city of London’s shield. Unfortunately, there is no record of what happened to it when the New Coal Exchange, despite being Grade II listed, was demolished in 1962 in order to widen the road.

New Coal Exchange under demolition

In order to put this tree-reverence business in perspective, a short digression is hopefully excusable here. Imbuing trees with special significance as embodying the spirit of a place, a powerful person such as a king, or even a whole tribe, goes back a long way in our traditions. In neighbouring Celtic Gaul they called such a sacred tree a bile. A grove of them was termed a nemeton in both countries. Oak trees in particular were objects of veneration, and when a peoples’ sacred oak died or was destroyed, their strength was believed to go with it. “Merlin’s Oak” in Carmarthen is a good example of this. I also think the upended and fenced-in oak tree discovered at Seahenge might once have represented a group of people who those who constructed it had defeated, or wished to control.

Dead mulberry sapling, Sayes Ct. Park

So, regardless of who actually planted it, the mulberry tree has become a fitting symbol of Sayes Court Garden and John Evelyn. Several older readers of this blog have commented on their fond childhood memories of tasting fruit from the tree, and there is clearly a strong affection for it among those who live or have lived in Deptford. If the Deptford High St anchor symbolizes the area’s dockland and maritime past, you could argue that the Sayes Court mulberry tree is an icon of its land-based history. Despite the press headline declaring that the mulberry “faces the chop” and can’t be saved, with some well-deserved tlc, it surely can. Even so, with an eye to the future, and since it is easy to propagate mulberries, Lewisham Council really should see to that this autumn. Oh, and let’s hope they look after any cuttings better than the one planted in the adjoining border that died of neglect recently…

51.145325

-1.987349